The Washington Navy Yard, authorized by the first Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert, in 1799, is the U.S. Navy’s oldest shore establishment. It occupies land set aside by George Washington for use by the Federal Government along the Anacostia River.

The original boundaries that were established in 1800, along 9th and M Streets SE, are still marked by a white brick wall, built in 1809, along with a guardhouse.

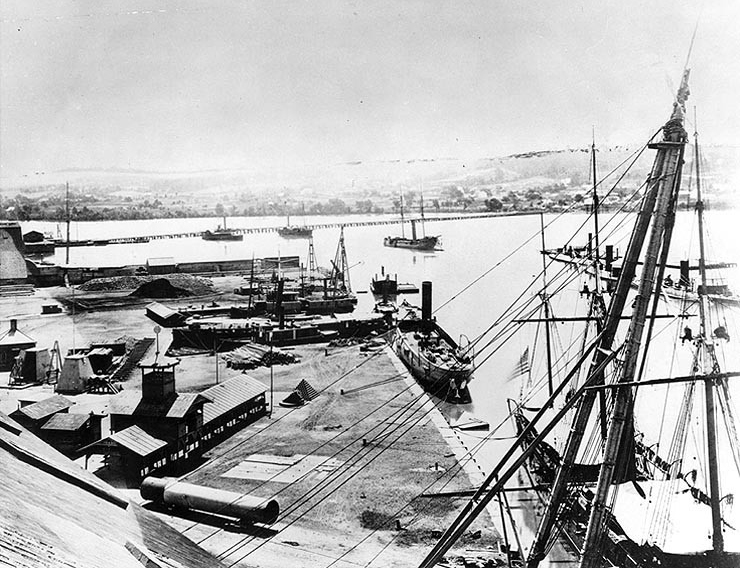

During its early years, the Navy Yard became the Navy’s largest shipbuilding and shipfitting facility. Twenty-two vessels were constructed on the Yard, ranging from small 70-foot gunboats to the Minnesota, a 246-foot steam frigate. In 1812, the USS Constitution came to the Yard to refit and prepare for combat action.

The War of 1812 found the Navy Yard a vital strategic link in the defense of the young capital city. On August 14, 1814, the British, under Admiral Sir George Cockburn and Major General Robert Ross, landed at Marlboro on the Patuxent River. Ten days later they brushed aside a hastily gathered American force at Bladensburg and marched into Washington. It became clear the Washington Navy Yard could not be defended and Captain Thomas Tingey, the Yard’s Commandant, with the concurrence of the president and the secretary of the Navy, ordered the Yard burned. All the stores that could not be evacuated, the unfinished Columbia and Argus, and most of the Yard’s buildings were consumed in the flames. Only the Latrobe gate, Tingey’s own quarters, adjoining offices, the barracks, and the small schooner Lynx escaped the fire. After the fire, looting by the local populace took its toll and Commodore Tingey recommended that the height of the eastern wall be increased to ten feet.

In May 1815, the Board of Naval Commissioners decided it was a disadvantage to have the Yard as a base and recommended it be limited to shipbuilding. Thus began a shift to what was to be the character of the Yard for more than a century: ordnance and technology. The Yard boasted one of the earliest steam engines in the United States, which was used to manufacture anchors, chains and steam engines for vessels of war.

By the 1850s, the Yard’s primary function had evolved into ordnance production. The engineering genius of Lieutenant John Dahlgren (who was to serve as the commandant of the Yard twice) nurtured this development.

With the start of the Civil War, the Washington Navy Yard would once again become an important player in the defense of the Nation’s capital. Commandant Franklin Buchanan resigned his commission to join the Confederacy, leaving the Yard to Commander John Dahlgren, who assumed command of the Yard on April 22, 1861. Holding Commander Dahlgren in the highest esteem, President Abraham Lincoln became a frequent visitor.

The Yard played a small but significant role in the events following the assassination of President Lincoln on April 15, 1865. Following the capture of eight of the conspirators, they were brought to the Yard and held on vessels anchored on the Anacostia River prior to their trails. The body of John Wilkes Booth was examined and identified on the monitor Saugus, moored at the Yard.

Following the Civil War, the Navy Yard continued to be the scene of technological advances. In 1886, the Yard was designated the manufacturing center for all ordnance in the Navy. Continuing ordnance production, the yard manufactured armament for the Great White Fleet and the World War I Navy, including the 14-inch naval railway guns used in France during World War I.

World War II found the Navy Yard as the largest naval ordnance plant in the world, with the weapons designed and built here used in every war in which the United States fought until the 1960s. Small components for optical systems and enormous 16-inch battleship guns were manufactured here. The Navy Yard was renamed the U.S. Naval Gun Factory in December 1945, and ordnance work was finally phased out in 1961. Three years later, on July 1, 1964, the activity was re-designated the Washington Navy Yard, and the deserted factory buildings began to be converted to office spaces.

The Navy Yard was also the scene of many scientific developments. Robert Fulton conducted research and testing on his clockwork torpedo during the War of 1812. Commodore John Rodgers built the country’s first marine railway for the overhaul of large vessels in 1822. John A. Dahlgren developed his distinctive bottle-shaped cannon that became the mainstay of naval ordnance before the Civil War. In 1898, David W. Taylor developed a ship model-testing basin, which was used by the Navy and private shipbuilders to test the effect of water on new hull designs. The first shipboard catapult was tested in the Anacostia River in 1912, and a wind tunnel was completed at the yard in 1916; the gears for the Panama Canal locks were cast at the Yard; and Navy Yard technicians worked on designs for prosthetic hands and molds for artificial eyes and teeth.

The Joint Committee on Landmarks has designated the Washington Navy Yard Historic District a Category II Landmark of importance, which contributes significantly to the cultural heritage and visual beauty of the District of Columbia.

The Washington Navy Yard has long served as the ceremonial gateway to the nation’s capital. The first Japanese diplomatic mission was welcomed to the United States in an impressive pageant at the yard in 1860. WWI’s Unknown Soldier’s body was received at the Yard, and Charles A. Lindbergh came to the Yard after his famous transatlantic flight in 1927.

Today, the Washington Navy Yard continues to be the “Quarterdeck of the Navy” and serves as the Headquarters for Naval District Washington, where it houses numerous support activities for the fleet and aviation communities.